Many children in the early stages of Perthes’ disease maintain good hip motion. The head displays plastic deformation at this stage. As movement is intact, the entire head spends time being molded by the acetabulum. This can be termed ‘passive containment.’ Preserved abduction of the hip (ensuring that pelvic movement is prevented) is generally used to guide whether a child is passively containing their hip.

In other children, the hip range of motion may be reduced, such that a portion of the femoral head (in particular the lateral column) does not enter within the acetabular dome. This is due to synovitis and pain, which results in adduction of the hip relatively ‘uncovering’ the lateral column.

This leads to abnormal loading forces and undesirable plastic changes. Many clinicians feel that children in this situation benefit from intervention to cover the head and allow more desirable molding. This can be achieved by surgically moving the femoral head or the acetabulum - this is termed ‘active containment.’

Historically, 2 years of bed-rest, spica casts, or one of various devices were used to brace the hip in abduction. These methods were cumbersome, and are less acceptable in modern times. Some units still advocate such treatment.

Active (surgical) containment – Younger patient

There are various treatment strategies. The authors feel that younger patients (typically under the age of 8) can be appropriately managed with either a varus femoral osteotomy or a salter osteotomy. The important pre-requisite for these procedures, which can be demonstrated by examination under anaesthesia and arthrography, is the absence of hinge abduction – If the femoral head has already undergone collapse, and a saddle has formed then either containment method would make this problem worse.

Varus osteotomy results in an immediate leg length discrepancy, with shortening of the involved limb. This shortening may improved the coverage of the hip as the pelvis dips over the femoral head. There is also shortening of the abductor moment arm and a resulting trendelenburg gait. In the younger child, there is usually sufficient remodeling potential for these issues to resolve, although they should be monitored and leg length inequality managed as appropriate. Some authors advocate trochanteric physeal arrest to prevent relative trochanteric overgrowth, which can lead to problems with impingement and the abductor moment.

A salter osteotomy is also a common means of containment. This operates on the ‘good side’ of the joint, rather than the damaged side. They provide anterior and lateral coverage, and therefore add containment to the areas most affected by Perthes’ disease. However, this osteotomy also lengthens the leg. This lengthening may have the effect to tilt the pelvis, which may conversely uncover the hip a little.

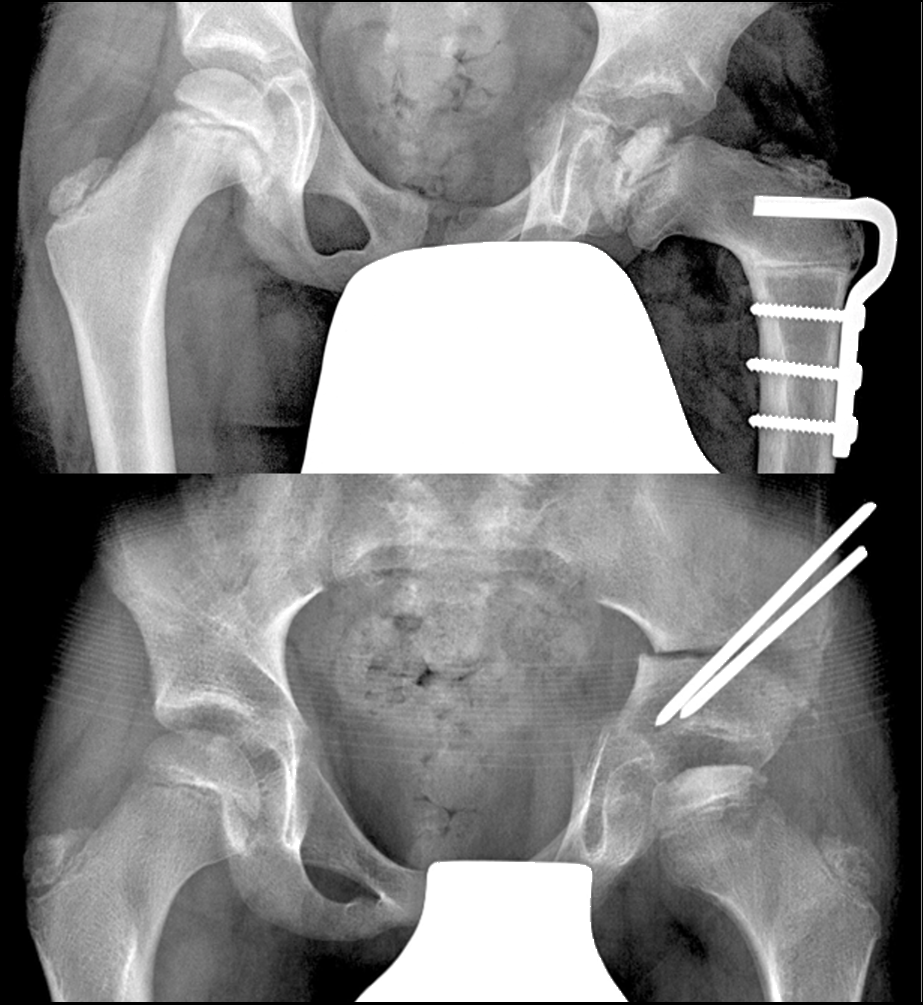

Radiographs demonstrating two of the common procedures used to treat early Perthes’ disease with surgical containment (Varus Osteotomy and Salter Osteotomy)

Active containment – Older patient

In older patients (typically over 8), we feel that the potential for proximal femoral remodeling is much lower and as such, we prefer to perform active containment procedures on the acetabular side. There are 2 broad types of pelvic osteotomy useful in Perthes’ disease;

- Reorientation – A Salter osteotomy may be used in Perthes’ disease with good outcomes. This hinges on the pubic symphysis and provides anterior and lateral coverage.

- Salvage – The shelf osteotomy has been employed in Perthes’ disease with encouraging results.

Reshaping (volume altering) are the other common type of pelvic osteotomy, however this should be avoided in Perthes’ disease. Unlike other paediatric hip pathologies, the acetabulum is typically uninvolved. Altering its shape and reducing its volume may have detrimental effects on the plastic femoral head.

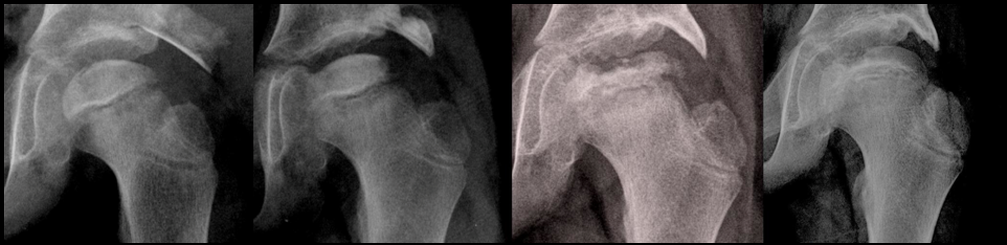

Active containment of an older child with Perthes, disease using a Shelf salvage procedure.