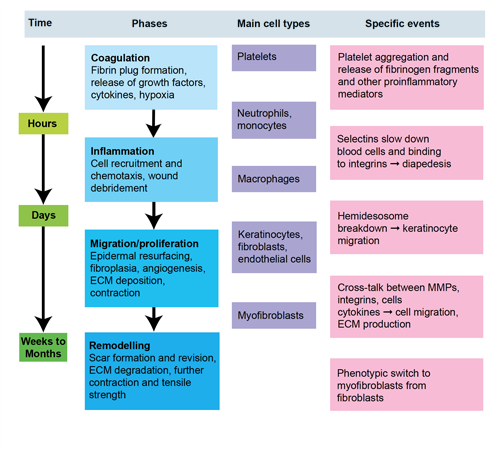

- It can be divided into three important phases:1,2

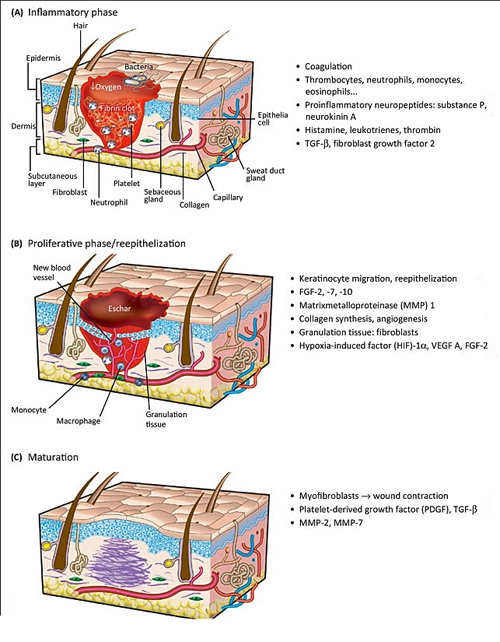

- The inflammatory phase

- The proliferative phase

- The maturation phase

Figure 1. Phases of wound healing

The inflammatory phase of wound healing (1–3 days)

- The inflammatory phase of wound healing is characterised by platelet accumulation, coagulation and the formation of a fibrin plug (which consists of platelets embedded in a meshwork of mainly polymerised fibrinogen (fibrin), fibronectin, vitronectin, and thrombospondin), increased permeability of the vessels adjacent to the wound, and leukocyte migration into the wound bed.

- During this phase the role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs), monocytes, and macrophages (tissue equivalent of the monocyte) are attracted to the wound site within 24–48 hours of injury by a number of chemoattractants including transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and complement components.

- T-cells also have a role in wound healing as growth factor producing cells and immunological effector cells.3 A number of cytokines, which are synthesised by T-helper (Th) lymphocytes have a profound influence in mediating the physiological response to tissue injury. The two major subsets of Th lymphocytes are the Th1 and Th2 cells, which are characterised by the presence of cell surface glycoprotein receptor cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4). CD8+ cells are involved in more specific cell targeting.

- Th1 cells secrete tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-2, which are key mediators of cellular immunity.

- Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-13, which are key mediators of the humoral immune system, and are predominantly responsible for stimulating the synthesis and release of antibodies from mature B-lymphocytes.

- Th3 cells are a minor subset of Th lymphocytes which secrete TGF-β and IL-10, and mediate a dampening of the overall immune response by inhibiting the action of other Th cells.

- An increased presence of T-cells and imbalances between CD4 and CD8 cells has been reported in chronic wound healing problems such as venous or diabetic ulcers.4

The proliferative phase of wound healing (3–10 days)

- The proliferative phase of wound healing involves a combination of four individual processes which take place simultaneously.

- Fibroplasia and angiogenesis within the wound bed collectively form both the granulation tissue matrix as well as the delicate new blood vessels which supply the developing tissue with essential nutrients.

- Re-epithelialisation restores the cutaneous barrier, and finally contraction of the wound by myofibroblasts reduces the wound size along with the resulting scar tissue.

- This process is also associated with a gradual decline in the number of pro-inflammatory cells associated with the early stages of the wound healing.

The matrix deposition and remodelling phase of wound healing (weeks to months)

- Matrix deposition and remodelling constitutes the longest phase in the wound healing process. It typically takes place over a period of months, as granulation tissue progressively devascularises and the collagen within the scar tissue undergoes dynamic remodelling.4,5

- Achieving equilibrium between collagen formation and degradation is extremely important in this process. There is sequential deposition of collagen, first type 3 and then type 1, and their hydroxylation peaks at around week 3. Collagen provides tensile strength, securing the matrix and scar tissue in situ, whereas collagenases degrade collagen in order to maintain the extracellular matrix. Together collagen synthesis and collagenolysis determine the functional strength of the scar tissue.

- The wound continues to contract with a maximal tensile strength about 60% of the previously unwounded skin.

Figure 2. Timing, main events and duration of phases