Examination of the foot and ankle

Problems with the foot and ankle given in the history usually comprise of deformity or pain. It is not uncommon for parents to bring children to the clinic with asymptomatic flatfeet or toe deformity

Inspect the child standing where possible, observing alignment from each plane. The medial longitudinal arch may be flattened (pes planus) but should easily reconstitute on Jack’s test. As the hallux is dorsiflexed the windlass mechanism results in tightening of the plantar fascia. Tiptoe standing has the same effect. The arch normally develops around the age of six but flexible flatfeet present in a range of severity and many require no treatment. Look for callosities over the talar head to suggest severe deformity. There may be tenderness over the sinus tarsi. A valgus heel should swing into varus on tiptoe standing. Fixed deformities include tarsal coalition or vertical talus.

Figure 12. Jacks test. The medial longitudinal arch is reconstituted with passive dorsiflexion of the hallux

A high arch is also examined with the child standing. Observe the position of the heel from behind. The Coleman block test will distinguish a forefoot- from hindfoot- driven deformity. Again it is helpful to demonstrate the test.

- Ask the child to stand barefoot on a block.

- Adjust the position of the foot so that the hind foot and lateral border remain supported but the first ray is allowed to drop.

- Observe the position of the heel from behind. The block test will accommodate a forefoot driven deformity and heel valgus should be restored. Residual varus suggests fixed deformity of the subtalar joint.

Looking at the posture of a parents foot can give significant information in the case of possible hereditary diagnosis such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

Remember to watch the child walk and look for aids or orthotics.

When sitting palpate the foot for areas of tenderness. Common paediatric sites of pain include those from the osteochondroses; over the heel, the navicular or second metatarsal.

Forefoot deformities should be examined for degree of correctability and range of movement at each joint should be noted.

Range of movement at the ankle and hind foot is recorded. Silfverskiöld test will demonstrate the role of gastrocnemius in any equinus contracture.

- With the knee fully flexed maximally dorsiflex the ankle.

- Ensure the foot doesn’t fall into valgus as this will give a false impression of maximum dorsiflexion.

- Slowly extend the knee, isolated gracilis tightness will result in reduced dorsiflexion of the foot as the knee extends.

Figure 13. Silfverskiöld test

Cavus deformities, clawing of the toes or asymmetry may suggest neurolomuscular aetiology. Full examination of the central or peripheral nervous system should be performed where appropriate

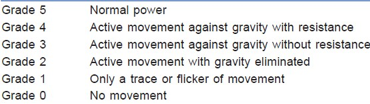

Examine individual muscle strength and grade according to the MRC grading system.

Remember to examine the spine for stigmata of dysraphism

Table 3.MRC Grading System ref: Medical Research Council. Aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system, Memorandum no. 45, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1981