- Primary malignant tumour arising from mesenchymal cells and producing malignant osteoid.

Incidence:

- Affects about 1/200,000 population.

- Accounts for 21% of malignant primary bone tumours (most common primary bone sarcoma).

- More common in male individuals.

- Bimodal age distribution:

Peak 1: 10–20 years (age of rapid growth).

Peak 2: 50–70 years (80% less than 30 years and those more than 40 years usually secondary to Paget’s).

- Third most common malignancy in adolescents, after leukaemia and lymphoma.

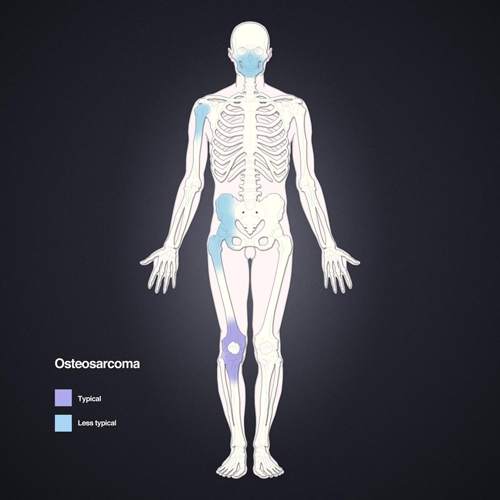

- Most common location is in distal femur/proximal tibia but other sites include: humerus, skull, jaw, and pelvis.

Types

Intramedullary (classic or ordinary) osteosarcoma.

Surface osteosarcomas:

- Parosteal osteosarcoma

- Periosteal osteosarcoma

- Intracortical osteosarcoma

Secondary osteosarcomas:

Telangiectatic osteosarcoma.

Figure 5. Osteosarcoma is mainly seen in bones with the fastest rates of growth such as long tubular bones of the limbs.

Clinical signs

- Pain which is worse at night.

- May have a painful, localised swelling without a definite edge, which can be attached to surrounding soft tissues.

- If vascular the mass may pulsate and feel warm.

- A fracture following minimal trauma, if secondary to osteosarcoma, is often a late feature of these tumours.

- Alkaline phosphatase is often greatly increased on blood test results.

Imaging

- X-rays:

- Commonly show bone destruction (blastic, destructive lesions) with associated cortical breach.

- Sun ray spicules/hairs on end patterns on radiographsand Codmans triangle(both caused by periosteal reaction) may be present.

- Moth eaten/fluffy appearance of bone on radiographs.

- A soft tissue mass may be visible.

- Joint spaces are rarely involved.

- The matrix produced by the tumour may be ossified/calcified in places.

- MRI is used to evaluate the tumour in detail, including staging.

- CT does not give any more information to MRI/plain radiographs apart from in lytic lesions where it can identify areas of mineralisation.

Pathology

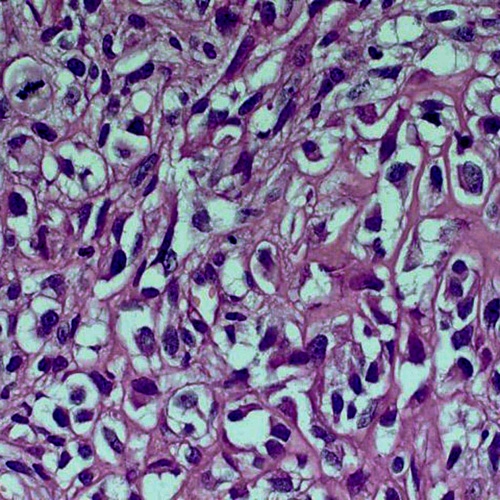

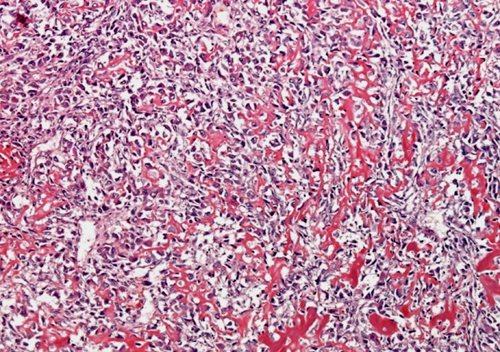

- Pleomorphic and anaplastic cell population with abundant fibrous and chondroid matrix..

- Stroma of spindle cells with numerous mitoses.

- Most are high grade aggressive tumours approximately 10 cm in diameter at diagnosis.

- 50% – osteoblastic

- 25% – chondroblastic

- 25% – fibroblastic

- Associated with areas of high osteoblastic activity e.g. the metaphysis, childrens’ bones, and bones affected by Paget’s disease.

- 20% are secondary to other conditions (e.g. Paget’s disease, enchondromas, osteochondromas, chronic osteomyelitis, irradiation, fibrous dysplasia, osteopetrosis and bone infarction).

- Usually occurs in the metaphysis and initially extends within the medulla but quickly perforates the cortex and causes a periosteal reaction.

- As the tumour mass expands new bone forms along vascular channels giving the appearance of sunray spicules.

- Metastasises via the blood stream to the lung and other bones.

- Carriers of the retinoblastoma tumour suppressor gene are at a high risk of developing osteosarcomas.

- In patients with Rothmund Thomson syndrome, there is a defect in the RECQL4gene on chromosome 8.

- These patients also are at high risk of developing osteosarcomas.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Figure 6 (a) and (b). AP and lateral radiographs left tibia. Classic osteosarcoma.A sclerotic lesion involving dia-metaphyseal region of the tibia with a wide zone of transition, osteoid matrix, periosteal elevation (Codman’s Triangle) and characteristic " Sunburst " type of periosteal reaction.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Figure 7. Fracture distal (metadiaphysis) femur with overriding and posteromedial displacement of the distal fracture segment. Small laterally displaced osseous fragment is also seen. The fracture margins are irregular. There are ill-defined lucencies reflective of lytic changes involving the distal shaft, metaphysis and epiphysis of the femur. Interrupted periosteal reaction (Codman triangle)is seen at the distal femoral shaft above the fracture site. Lobulated soft tissue mass density is seen surrounding the fracture and effacing the adjacent fat planes. Most important for candidates is too realise that this is a pathological fracture and not a de nova fracture.

Differential diagnosis

- Post traumatic callus or myositis ossificans.

- Stress fracture - pathology may look similar.

- Osteomyelitis or syphilis

- Benign bone tumour may have a similar appearance especially if X-rayed early.

- Ewing’s sarcoma

- Bone metastasis

- Aneurysmal bone cyst

Treatment

- T10 regimen (methotrexate, vincristine, adriamycin) has approximately 60–75% survival.

- 45% of patients with the T10 regimen achieve a 100% kill rate and therefore 100% survival.

- Survival beyond 10 years is regarded as cured.

- Regimen continued postoperatively or changed to cisplatin depending on histology ®92% of patients are disease free at 2 years.

- Chemotherapy continues for 12 months in 4/52 cycles.

- Intra-arterial chemotherapy is used in some centres. This is when increased doses of the drugs are given at the site of the lesion but there is no evidence that this changes the outcome as multiple feeding vessels of the tumour may be missed.

- Radiotherapy is used for palliation of local pain and to treat surgically inaccessible lesions and painful metastatic deposits.

- Osteosarcomas are relatively radio-resistant but radiotherapy may also be used preoperatively to decrease the size and vascularity of the tumour.

- Prophylactic irradiation of the chest has not been shown to be effective.

Surgery:

- Aggressive resection including limb amputation with adjuvant chemotherapy may be necessary.

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be used for a number of weeks before surgery is attempted as a limb salvage procedure. Postoperative chemotherapy is also required in these cases.

- Limb salvage requires ability to:

- Preserve nerves.

- Preserve or reconstruct vessels.

- Preserve sufficient muscle for functional motor power and soft tissue coverage.

- Achieve safe, tumour-free margins (wide).

- Allografts

- Endoprosthesis

- Expendable bone (fibula, ilium)

- Rotationplasty

Prognosis

- Untreated cases have a 95% death rate in 2 years.

- 10% have macro-metastases at presentation; 90% have micro-metastases.

- Even with metastatic (stage 3) disease,5 year survival now is 30–40% (10–20% with surgery alone).

Prognostic factors:

- Age – adults do worse.

- Size of primary tumour (big is bad).

- Location (proximal worse than distal).

- Type:

Parosteal – tend to be more low-grade tumours and therefore these have a better prognosis.

Intraosseous (classic) osteosarcomas have a good prognosis.

- Stage

- Response to chemotherapy:

80–90% 5-year disease-free survival in good response patients.

60% 5-year disease-free survival in patients with poor response rates.

- More than 16 metastatic deposits is considered to have a poor prognosis.

- Pathological fracture(s) do not affect prognosis.

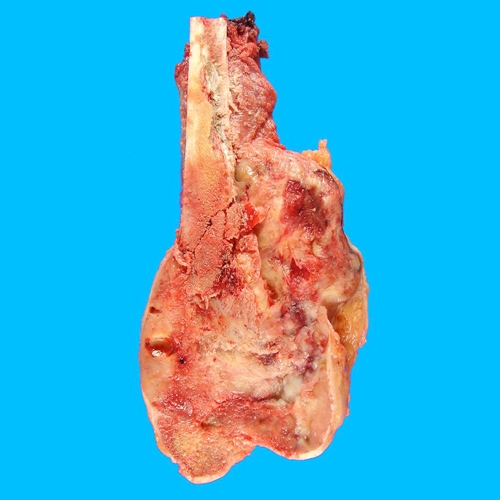

Figure 8.Gross pathology distal femur.

Figure 9. In addition to mitosis (upper left) and cellular atypia (everywhere), which are usual; one should see the atypical osteoid (upper right) to make the diagnosis.

Figure 10. Lace-like osteoid deposited in between heavily anaplastic tumour cells.